Periodontal disease: the portrait of an epidemic

Introduction

Periodontal disease is conventionally defined as an inflammatory disorder involving both soft and hard periodontal structures (1). The early phase, conventionally defined as gingivitis, is characterized by a modest and self-limiting inflammation of periodontal structures. When the local inflammation progresses, the disease evolves towards periodontitis, which has been defined by the 1999 International Workshop on Classification of Periodontal Diseases as a microbially-associated and host-mediated inflammation, resulting in loss of periodontal attachment (2). In the following 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions, it was then specified that the diagnosis of periodontitis shall be based on clinical attachment loss (CAL) by circumferential assessment of erupted dentition using standardized periodontal probes with reference to cemento-enamel junction (3). According to the pathophysiological basis, periodontitis can be classified in three different forms, i.e., periodontitis, periodontitis associated with systemic diseases and necrotizing periodontitis. Periodontal disease progressively evolves when left untreated, thus causing several local complications such as the development of deep periodontal lesions, periodontal bone and tooth loss, up to masticatory failure (3).

It has been recently hypothesized that some bacteria responsible for periodontitis may actively enter the circulation from periodontal tissues, dislocate in many organs and tissues, thus enhancing the risk of developing pathologies characterized by inflammatory/infectious components (4). These typically include various types of malignancies (especially digestive tract, pancreatic, prostate, breast, uterus, lung, esophagus and oropharyngeal cancers, along with lymphomas) (5), cardiovascular disease (6), venous thromboembolism (7), diabetes (8), rheumatic disorders (9), as well as dementia (10), which all cumulatively represent the most common worldwide pathologies (11). Such an increasingly strengthening association between periodontal disease and human pathologies shall hence drive the establishment of efficient healthcare interventions aimed at preventing the development of periodontitis as well as at mitigating its potential impact on human health and ultimately limiting its potentially adverse clinical, societal and economic consequences. Nevertheless, efficient planning of preventive and curative healthcare interventions always requires to be based on accurate epidemiological basis, so that the target populations could be more efficiently identified and managed.

Some generic articles have been published on the worldwide epidemiology of periodontal disease over the past two decades (12-16), whilst no recent and systematic overview, based on large and reliable disease repositories, exists to the best of our knowledge. Therefore, in this article we aim to provide an updated and comprehensive overview on the worldwide burden of periodontal disease.

Methods

Our approach for estimating the epidemiologic burden of periodontal disease encompassed an electronic search in the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) database, the largest worldwide repository of health-related information maintained by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (17). Briefly, this free online version of the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2017 (GBD 2017) database now includes comprehensive information on 354 human pathologies garnered from 195 different countries and territories, in the period between the years 1990 and 2017 (18).

Specific electronic searches were hence performed in GHDx using the specific keyword “periodontal disease” [International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes K05.0 and K05.6, along with ICD-9 codes 523.0 and 523.9]. According to the GBD 2017 collaborators, data on periodontal disease has been collected using the definition provided by Page and Eke, in 2007 (19), from as many as 441 site-years in 81 different countries belonging to all the main seven GBD super-regions (i.e., South-East Asia, East Asia & Oceania; South Asia; Central Europe, Eastern Europe & Central Asia; North Africa & Middle East; Sub-Saharan Africa; Latin America & Caribbean; High Income). Data have then been modelled using the Bayesian meta-regression tool DisMod-MR 2.1, adjusting the final estimates for prevalence of edentulism, whereby edentate subjects are systematically excluded from studies on periodontal disease (18).

The electronic searches were complemented with additional keywords such as “metric” (“rate”, expressed as cases per 100,000), “measure” (“incidence”, “prevalence” and “DALYs”, i.e., disability-adjusted life year), “year” (from year “1992” to year “2017”), “sex” (“both”, “male” and “female”), “age” (from “<1” to “≥90” years) and “location” (WHO regions, encompassing “Africa”, “Eastern Mediterranean”, “Europe”, “Americas”, “South-East Asia” and “Western Pacific”). The results of our searches were imported into a Microsoft Excel file (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and then analyzed using MedCalc statistical software (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). When necessary, the risk of periodontal disease was expressed as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, under the terms of relevant local legislation. Ethics board approval is unnecessary at the local institution (University of Verona) for articles based on electronic searches in free scientific databases.

Results

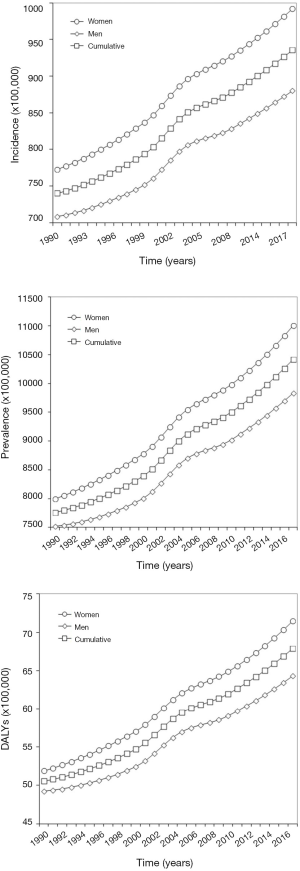

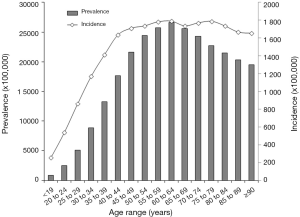

The temporal trend of periodontal disease during the past 3 decades in both sexes is shown in Figure 1. Incidence, prevalence and DALYs curves follow a virtually identical path, with estimates that have constantly increased during the past 3 decades. The cumulative incidence has grown from 740 to 936 cases per 100,000 (+26%), exhibiting a slightly higher escalation in women (from 772 to 992 cases per 100,000; +28%) than in men (from 708 to 880 cases per 100,000; +24%). The cumulative prevalence has also increased by 34% during the past 3 decades (from 7,762 to 10,420 cases per 100,000), again with a slightly higher escalation in women (from 8,002 to 11,009 cases per 100,000; +38%) than in men (from 7,572 to 9,835 cases per 100,000; +31%). This remarkable epidemiologic burden now makes periodontal disease the 12th more prevalent pathology around the world. The temporal trend of DALYs (cumulative DALYs are 68 per 100,000 in 2017, 71 in women and 64 in men, respectively) closely mirrors that of prevalence. According to these figures, women have 13% higher risk of incident (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.03–1.24; P=0.009) and prevalent (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.10–1.17; P<0.001) periodontal disease, respectively. The age distribution of both incidence and prevalence of periodontal disease is shown in Figure 2. Both epidemiologic curves exponentially increase after 19 years of age. Prevalence clearly peaks between 60–64 years and then gradually decreases, whilst incidence remains virtually stable after 40 years of age throughout the elderly. The risk of suffering from periodontitis is hence 67% higher in older people (i.e., aged 65 years or older) than in younger subjects (OR, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.63–1.71; P<0.001).

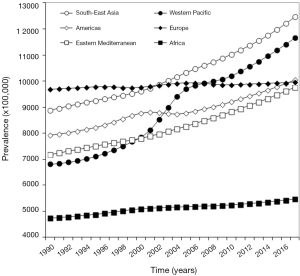

The geographical evolution of the prevalence of periodontal disease during the past 3 decades is summarized in Figure 3, which clearly shows that the highest disease burden is now recorded in South-East Asia (12,463 cases per 100,000) and Western Pacific (11,653 cases per 100,000), followed by the Americas (10,047 cases per 100,000), Europe (9,965 cases per 100,000) and Eastern Mediterranean (9,757 cases per 100,000), whilst the prevalence is the lowest in Africa (5,469 cases per 100,000). Regarding the temporal trend, Western Pacific has displayed the largest increase during the past 3 decades (+70%), followed by South-East Asia (+40%), Eastern Mediterranean (+36%), Americas (+27%) and Africa (+15%), whilst the prevalence has remained virtually stable in Europe (+3%).

Discussion

Taken together, the current epidemiological estimates of periodontal disease identified with our analysis concur to define the portrait of a growing epidemic, with incidence, prevalence and years lost for ill-health or disability that have all constantly increased during the past three decades. According to the data of GHDx repository, the largest database of human pathologies worldwide, periodontal disease is now the 12th more prevalent condition around the world, being included among the top ten more prevalent pathologies in all WHO regions except Africa. Its burden is slightly higher in the female sex and tends to gradually increase in parallel with ageing, with a definitive prevalence that is 67% higher in the elderly. Although it may seem that the degree of “unhealthy life” due to periodontal disease is relatively modest (i.e., 68 DALYs per 100,000), this estimate is now almost identical to that caused by lip and oral cavity cancer (69 DALYs per 100,000) and higher than that of other conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (46 DALYs per 100,000), larynx (43 DALYs per 100,000), uterus (28 DALYs per 100,000) and thyroid (15 DALYs per 100,000) cancers (17), which are typically perceived as more invalidating conditions by the general population as well as by many policymakers, healthcare administrators and healthcare professionals.

These concerning estimates, both in terms of current prevalence as well as considering the recent escalating burden of periodontal disease, contribute to raise many healthcare concerns associated with the important local (oral cavity) consequences, but also for the notable associations that have recently been reported between periodontitis and severe organic diseases. Several lines of evidence now support the existence of a strong association between periodontal and cardiovascular diseases. The results of the recent Periodontitis and Its Relation to Coronary Artery Disease (PAROKRANK) study, which included as many as 1,610 subjects (half being diagnosed with myocardial infarction) undergoing standardized dental examination, showed that periodontal disease was more frequent in patients than in controls (43% vs. 33%; P<0.001) (20). In fully-adjusted multivariable analysis, the risk of myocardial infarction was found to be 28% higher in subjects with periodontal disease than in those without (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.03–1.60). A possible association between periodontal disease and venous thromboembolism has also been described by Cowan et al. Briefly, the 7,856 participants to the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study were followed up for a mean period of 12.9 years (7). Periodontal disease was found to be more frequent in patients with incident venous thromboembolism than in those without, so that periodontitis was associated with a ~90% higher cumulative risk of venous thrombosis [hazard ratio (HR), 1.91; 95% CI, 1.19–3.08]. In another study, Winning et al. carried out detailed periodontal examinations in 1,331 diabetes-free subjects, who were then followed up for a mean period of 7.8 years (21). In multivariate analysis the risk of incident diabetes was 69% higher in patients with moderate or severe periodontitis than in those without (HR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.06–2.69). Interestingly, an association between periodontal disease and gestational diabetes mellitus has also been recently evidenced by Kumar et al. (22). Briefly, 584 primigravidae enrolled between 12–14 weeks of gestation were concomitantly subjected to periodontal examination and 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Notably, not only the fully-adjusted risk of gestational diabetes mellitus was 2.8-fold higher (HR, 2.85; 95% CI, 1.47–5.53) in women with periodontal disease than in those without, but the presence of periodontitis was also associated with 2.2-fold higher risk (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 0.86–5.60) of developing pre-eclampsia. As regards cancer, Corbella et al. have recently published the results of a comprehensive meta-analysis (5), in which they have explored the potential association between periodontal and malignant diseases according to available literature data. The results of this meta-analysis convincingly showed that periodontitis is associated with a 14% higher risk (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.04–1.24) of developing all types of cancers, especially malignancies of oesophagus and oropharynx (HR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.30–3.90), uterus (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.16–4.18), pancreas (HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.21–2.52), digestive tract (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.05–1.72), prostate (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.04–1.51), lung (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.06–1.45), and breast (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.00–1.23), as well as with enhanced risk of lymphomas (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.11–1.52) and other hematological cancers (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.11–1.53).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the combination of our analysis on the GHDx repository with the growing evidence that periodontal disease is associated with both local and generalized complications is in keeping with the current view of periodontitis as a major public healthcare issue (23), and further contributes to reinforce the concept that a holistic preventive and curative approach shall be planned for lowering the otherwise unfavourable clinical, societal and economic consequences of periodontal disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jphe.2020.03.01). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The data in this article are taken from a public database, so ethical review is exempt.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Chapple ILC, Mealey BL, Van Dyke TE, et al. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol 2018;89:S74-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- 1999 International Workshop for a Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions. Papers. Oak Brook, Illinois, October 30-November 2, 1999. Ann Periodontol 1999;4:1-112. [PubMed]

- Tonetti MS, Greenwell H, Kornman KS. Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Periodontol 2018;89:S159-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iwai T. Periodontal bacteremia and various vascular diseases. J Periodontal Res 2009;44:689-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corbella S, Veronesi P, Galimberti V, et al. Is periodontitis a risk indicator for cancer? A meta-analysis. PLoS One 2018;13:e0195683 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carrizales-Sepúlveda EF, Ordaz-Farías A, Vera-Pineda R, et al. Periodontal Disease, Systemic Inflammation and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Heart Lung Circ 2018;27:1327-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cowan LT, Lakshminarayan K, Lutsey PL, et al. Periodontal disease and incident venous thromboembolism: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. J Clin Periodontol 2019;46:12-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Badiger AB, Gowda TM, Chandra K, et al. Bilateral Interrelationship of Diabetes and Periodontium. Curr Diabetes Rev 2019;15:357-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bingham CO 3rd, Moni M. Periodontal disease and rheumatoid arthritis: the evidence accumulates for complex pathobiologic interactions. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2013;25:345-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dioguardi M, Gioia GD, Caloro GA, et al. The Association between Tooth Loss and Alzheimer's Disease: a Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Case Control Studies. Dent J (Basel) 2019. doi:

10.3390/dj7020049 . - Mattiuzzi C, Lippi G. Worldwide disease epidemiology in the older persons. Eur Geriatr Med 2019; [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed]

- Albandar JM, Rams TE. Global epidemiology of periodontal diseases: an overview. Periodontol 2000 2002;29:7-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Albandar JM. Epidemiology and risk factors of periodontal diseases. Dent Clin North Am 2005;49:517-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hugoson A, Norderyd O. Has the prevalence of periodontitis changed during the last 30 years? J Clin Periodontol 2008;35:338-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Susin C, Haas AN, Albandar JM. Epidemiology and demographics of aggressive periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 2014;65:27-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Papapanou PN, Susin C. Periodontitis epidemiology: is periodontitis under-recognized, over-diagnosed, or both? Periodontol 2000 2017;75:45-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange. Available online: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool. Last accessed, February 10, 2020.

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018;392:1789-858. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol 2007;78:1387-99. [Crossref]

- Rydén L, Buhlin K, Ekstrand E, et al. Periodontitis Increases the Risk of a First Myocardial Infarction: A Report From the PAROKRANK Study. Circulation 2016;133:576-83. [PubMed]

- Winning L, Patterson CC, Neville CE, et al. Periodontitis and incident type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Periodontol 2017;44:266-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kumar A, Sharma DS, Verma M, et al. Association between periodontal disease and gestational diabetes mellitus-A prospective cohort study. J Clin Periodontol 2018;45:920-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dumitrescu AL. Editorial: Periodontal Disease - A Public Health Problem. Front Public Health 2016;3:278. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Nocini R, Lippi G, Mattiuzzi C. Periodontal disease: the portrait of an epidemic. J Public Health Emerg 2020;4:10.